Earlier this year Philip Duff and Jean-Sebastien Robicquet began a mission to re-create a gin recipe from 1495. With the help of a Magnificent 7-esque bunch of experts they embarked on an adventure and now Philip shares his story with BarLifeUK.

“You really set it on fire??”

Jean-Sebastien Robicquet, owner and master distiller of EWG Spirits & Wine, looked just a little incredulously at Didier, the avuncular gentleman in charge of day-to-day production at EWG’s headquarters in Cognac. We’d asked Didier to distill something for us, and the recipe included a handy way to test the strength of the distillate: soak a cloth in the distillate, and if it caught fire, it was the correct alcoholic strength. But then, that recipe was from 1495….

Let’s start at the beginning.

519 years ago, someone very rich was looking for a way to show off exactly how rich he – or she – was. Living in – presumably – a great big fuck-off house, somewhere in the area of Arnhem – Apeldoorn in the Netherlands wasn’t enough. Having a load of household servants wasn’t enough.

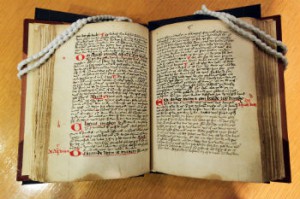

It was time to spend buckets of money on the ultimate, rare, cutting-edge technology: self-publish a book of household recipes.A book that would be handwritten, by a hired scribe, on the most expensive paper available, using iron-gall ink collected from oak galls (created when a wasp stings a tree, fact fans!).

Centuries later, that book would find its way into the collection of wealthy (he was personal physician to three kings) doctor Sir Hans Sloane, and be left to the British nation (along with 99,999 other items) on Sloane’s death in 1753, eventually forming part of the initial collection of the British Library. 243 years after that, in 1996, a respected professor of distilling named Eric van Schoonenberghe published “Jenever in de Lage Landen” (“Genever in the Low Countries”), which is the very last word not only on genever’s storied history, but indeed on distilling in Europe.

In it, van Schoonenberghe details this recipe from 1495, offhandedly noting that “this may be the oldest recipe in the world for gin”. And five years after that, yours truly picked up a copy of Genever in the Low Countries.

I was – indeed I am – a huge fan of genever and almost everything published, even in Dutch, is full of errors, so finding Genever in the Low Countries was like finding a fellow professional drinker at an office Christmas party. Seven years later, in 2008, I’d recently taken on EWG Spirit and Wine as a client, and was writing the education program for their flagship grape-based gin, G’Vine.

All this 1495 malarkey was gold – historical evidence of grape-based gin (didn’t I mention that? Oops! The 1495 recipe was based on twice-distilled wine, almost certainly from St Jean d’Angely, the Cognac region that’s also home to G’Vine).

Almost a year ago, Jean-Sebastien asked me what I thought of making this recipe. I giggled like a tickled lunatic. I’d translated the recipe’s nuts and bolts for him and the team years before; the twice-distilled wine, the bad-ass botanicals (nutmeg, juniper, cloves, galanga, ginger, grains of paradise, sage, etc). But I hadn’t bothered translating all of it, because it was frankly bonkers.

You were supposed to seal the still helmet with “a mix of flour and water” and condense the distillate “by laying strips of linen soaked in water” on the outflow pipe. Plus, helpfully, the recipe explained you could test the strength of what you’d made by seeing if a strip of cloth soaked in the distillate caught fire. I couldn’t help wondering if that was the kind of job they gave to the most junior knave in the scullery.

Bonkers it may have been, but if you’re doing something crazy, there’s always a Frenchman who’ll help you out, and that man was Jean-Sebastien. He allowed me to press-gang Dave Wondrich into coming along, and gave us the run of EWG’s test distillery at their 14th century farmhouse HQ, Villevert, in Cognac. By the time we got there, Didier had already run a few distillations, and we got the feeling he was really enjoying this.

A normal day for Didier is trying to work out how to make an additional 500,000 cases of Ciroc (which EWG produce for the brand’s owner, Diageo) on time, or ensure that the bottling plant keep G’Vine Floraison and G’Vine Nouaison gin separate. Or possibly try to work out why someone in Jalisco is shouting at him on the phone in Spanish. (Probably something to do with Excellia tequila, a joint venture between Jean-Sebastien and Carlos “Tapatio” Camarena).

“You really set it on fire??”

Didier nodded, as if this was the most normal thing in the world. I suppose it was; he’s used to following recipes, and this was in the recipe. Myself and Dave decided to temporarily halt the whole setting-fire-to-stuff thing while we worked out the recipe. It gave exact amounts of everything, but what would a crafty distiller have left out?

Sugar? Nope, didn’t really exist in Europe back then. Cutting heads and tails? For sure. Barrel-aging? Nope, barrels weren’t widely used for aging or storage until a few hundred years later. The recipe hinted at using wine lees and / or pomace, so we used a lees-distilled Ugni Blanc distillate as the base and blended in a little Ugni Blanc marc to approximate pomace.

We slowed the state-of-the-art 20-liter copper test stills down to a snail’s pace and tried to take our cuts at lower alcoholic strengths, to simulate what we had to imagine were inefficient stills back then (remember the bit about sealing the helmet with flour and water?).

As soon as we were happy with the result, myself and Dave went out to celebrate with Negronis and wine, then more wine, and finally some Negronis to finish up.

I shipped him back to Brooklyn, popped over to London to see the original manuscript (it’s amazing – get a reader’s card for the British Library and go take a look yourself) and then I imported another impressively-bearded Dave (Broom, from exotic Brighton), gaz Regan, The Cocktail Lovers’ Gary Sharpen and Drinks International’s Holly Motion. After a quick visit to the Genever Museum in Holland which had sparked my interest all those years ago, we headed to Villevert for phase two; making an updated version of the recipe, using the liquid Dave Wondrich and I had agreed on the previous week.

Jean-Sebastien, you see, displaying an urgent motivation I’d only previously observed in him when he was making himself a Negroni, had decided that what was now called Gin 1495 would be presented with two versions; the exact recipe replica, and the one that myself and the Week 2 team were tinkering with, to be called Interpretatio.

Both would be bundled together and – this was the awesome bit – never available for sale. Instead, they’d be auctioned for charity (get yours now! details here) and donated to both spirits museums like Museum of the American Cocktail and the Ginstitute, and offered to gin brand visitor experiences like those of Tanqueray, Beefeater and Bombay Sapphire, if they’d like to have it.

“What, competitors to G’Vine? Their visitor experiences?”

I raised an eyebrow. But Jean-Sebastien was adamant. Gin 1495 was in the world, his gift to the whole category.

Well, dear reader, myself, Regan, Broom, Sharpen and Motion experimented until we were blue in the face (and until Didier looked like he was regretting not taking a nice easy gig at a cognac house). We did high-sage. High-juniper. High-citrus. We fiddled and voted and discussed and ate heroic portions of steak tartare and snails and rather decent claret. We sneaked out of the hotel and drank beer and cognac. We went back to the hotel and drank cocktails. We went back to Villevert and narrowed it down to three. Then two. Then just one; hints of citrus and iris, more juniper, less nutmeg. Interpretatio was done. Verbatim (the exact replica) was done. Gin 1495 was a go.

One of the most rewarding, fascinating and bonkers journeys of my career, starting almost fifteen years ago, had come to fruition. A launch in London followed, and I hear rumblings of Germany, Asia and, God help us, America. Nice – but more important to me is that people can now drink a little bit of liquid history, and connect to that distiller – male? female? kitchen staff? the favoured employee? – in that big house, in Holland, 519 years ago.

Not a bad a day at the office.