One of my favourite ever drinks quotes was from Gary Regan, on the Long Island Ice Tea.

He described it as “the best ‘monkey at a typewriter’ cocktail ever invented”. Throwing 4 different base spirits and a triple sec together in one drink, in equal measures, simply shouldn’t work, and it is blind luck that it did (sort of).

At any rate it was an extraordinarily bad way of going about putting a drink together.

To systematically come up with decent cocktail recipes is a complex procedure, and it is not simply a case of does this taste nice with that. Any time we are attempting to create a good drink, we need to apply a series of criteria.

When tasting a combination of flavours, we must first decide what kind of drink would suit the flavours we are playing with best, be it long or short, aperitif or digestif, and then we need to consider:

- The intensity of flavour of the drink,

- How well the drink is balanced,

- Is there a pleasant complexity to the drink,

- How does the character of the drink change with time in the mouth.

- Is this progression of flavours in the mouth smooth?

And we must consider all of these and more in tandem. And when this is all done we need to step back and ask if the drink has that something special.

One of the finest cocktail books of all time was not written by a bartender. It was written by a lawyer by the name of David Embury.

What sets this book apart for me is that when discussing particular cocktails he does not simply give a recipe, which pretty much every other cocktail book written would do. He discusses why we use the ingredients in the proportions we do, and why we should sometimes change these proportions to suit a particular occasion.

This understanding of how and why we mix ingredients the way we do is not discussed and analysed enough, and it is something I would like to start to address here, with a discussion of factors which affect a drink’s intensity of flavour.

Intensity of flavour

A good drink must have a reasonable intensity of flavour, but it must not be too intense.

Obviously the level of intensity required is also governed by the type of drink we want to create. A Manhattan be more intensely flavoured than a Collins.

There are various factors which affect the intensity of flavour in a drink, and these must all be considered in the overall recipe.

For this first article, we will look at sweetness.

Sweet

The sweeter a drink is, the more intense all the flavours in the drink will be. This is a fairly hard and fast rule. As a species, we require sugars for energy, and as a result we have evolved so that when we ingest sugar, our taste receptors become more active, and intensity of flavour increases as a result.

Sugars also helps smooth the aggressive edges of sour and bitter tastes such as with spices or citrus peels and juices.

However we can not just keep adding sugar to a drink, as it will become sickly and too intense, so if we are using gomme made with regular sugar (sucrose) there is an optimum point somewhere between 5ml and 30ml depending on the other flavours or the way the drink is served, straight up, on the rocks, frozen, short or tall.

A short drink with spirit, sugar and a twist will not need a lot of sugar. For those of you who make a lot of Old Fashioneds, you will know that if you add a little too much gomme, you will probably end up needing to add a splash of bourbon at the end to reduce the sweetness levels.

Conversely a tall drink served frozen with cream added will need quite a bit of sugar, as dilution, temperature, and the cream will all have the effect of reducing flavour intensity, and so we need more sugar to keep it up (flavour intensity that is, grow up).

Now to get a little more complicated:

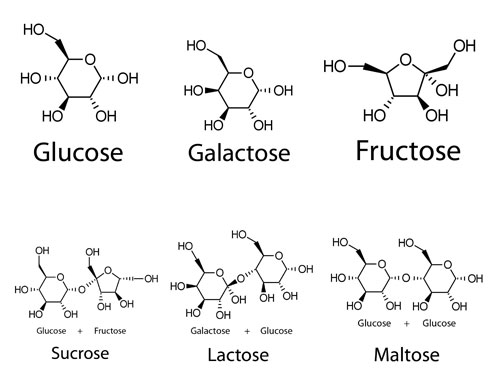

All sugars are part of a huge family of compounds called carbohydrates. All carbohydrates have one thing in common, and that is the ratio of Carbon to Hydrogen to Oxygen in them is 1:2:1. This makes them an efficient way of storing energy. The sugars we are most interested in are either a single ring (a monosaccharide like fructose, glucose, galactose) or 2 rings joined together (a disaccharide like sucrose, maltose, or lactose).

Sucrose is formed by joining together glucose and fructose. Maltose is formed by joining 2 glucose molecules. It is the sugar formed when Barley is “malted”. Starch and Cellulose are huge molecules made up of thousands glucose molecules bonded together.

All these different sugars have different sweetness intensities. Of the monosaccharides, Fructose is sweeter than glucose, which is in turn sweeter than galactose. Of the disaccharides, sucrose is sweeter than maltose, which is sweeter than lactose.

[ultimatetables 1 /]

For anyone who doesn’t know what Galactose is, Glucose and Galactose are almost identical, the only difference being their 3 dimensional arrangement of functional groups. Due to this tiny difference, Glucose is twice as sweet as Galactose and far easier for the body to digest. Lactose is made by joining glucose and galactose together and it is the Galactose present which is responsible for Lactose intolerance. Galactose is also one of the sugars that make up hemicellulose, one of the building blocks of oak, and is responsible when barrels are charred for some of the bread and caramel aromas in aged spirits.

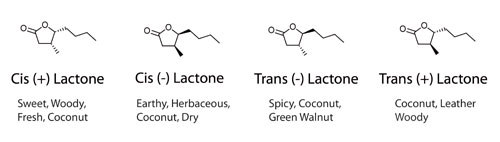

This 3 dimensional arrangement of groups, or stereoisomerism also means that the 4 stereoisomers of Oak Lactone have markedly different smells:

This has nothing to do with sweetness and intensity of flavour, but the cocktail nerd in me had to point out the parallel. Moving on…

Gomme syrup is made with sucrose. Sucrose has a unique property in that its flavour is pure sweetness, it does not have any other character.

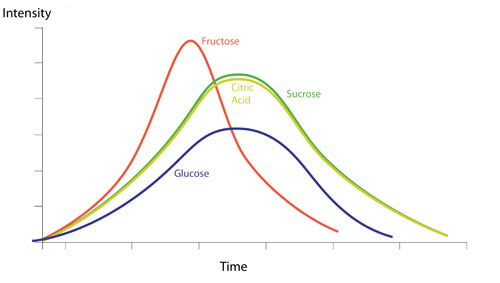

A majority of citrus cocktails employ sucrose based sweet ingredients, be that a gomme or a liqueur. It tends to work better in these cocktails than glucose or fructose, as the time-intensity curve for lemon and lime juice is almost identical to that of sucrose, whereas with fructose, the sweetness is faster to develop on the mouth so we get a peak of sweetness before the peak of sour, and with glucose, not only does the peak of flavour come late, but it also half as sweet as sucrose, so we need to add almost twice as much glucose to balance the citrus and this can result in an unpleasantly viscous drink.

An example of the fructose vs sucrose effect can be seen if one makes a Tommy’s Margarita.

If you try and make one with agave syrup that has not been mixed with water and gomme, it is not as good a drink as one that has.

This is not to do with the higher sweetness of the agave, but because the main sugar in agave is fructose.

The flavour profile of this drink would therefore be slightly disjointed, as one would taste a peak of sweetness from the fructose before a peak of sourness from the lime.

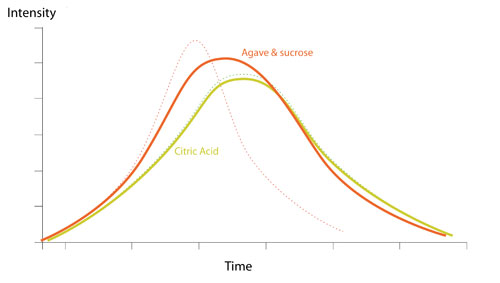

If we use agave that has had gomme, or sucrose added to it, the secondary peak of sourness is smoothed by the sucrose, as its intensity peak occurs at the same time as the lime juice.

If we only used sucrose, and no agave, we would get none of the beautiful interaction between the agave syrup and the herbaceous, vegetal notes in the tequila.

Another example of the hidden complexity within an outwardly simple great cocktail.

This is also a good reason for adding sugar and water to honey to make honey gomme for cocktails. The addition of sucrose again makes the gomme blend better with citrus juices than pure honey.

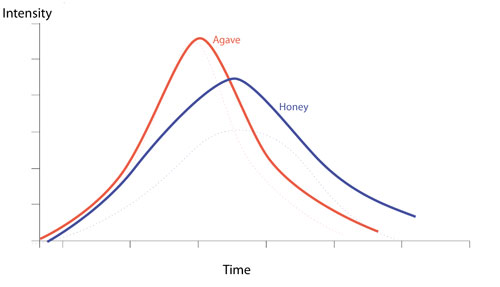

The combination of sugars in natural products such as Honey and Agave affects their sweetness time intensity curves and this in turn affects the uses we can make of them. Let us consider agave and honey.

Agave is made up of predominantly fructose with a small percentage of glucose. Honey has roughly equal amounts of fructose and glucose, with a small amount of maltose and sucrose. Let us now look at how this might effect their time intensity curves.

So we can see that agave has a peak in intensity of sweetness much sooner than honey and its sweetness dies away quickly in comparison. This lend itself to use with unaged spirits.

Honey on the other hand has a long sweet finish due to the glucose, maltose and higher sugars, and this works better with aged spirits.

So Honey is a perfect match for scotch whiskey, whereas agave is a perfect match for blanco tequilas.

Part Two of Andrew Campana’s series – The DNA of a Cocktail will be published soon.