Bangkok, June 1999.

It is 10pm, and the Khao San Road is alive with coloured festoon lights and neon bar signs. The street-side restaurants are full of backpackers watching bootleg DVDs of The Matrix on fuzzy TV screens as they eat Pad Thai. Every second bar is playing Fatboy Slim. I weave my way through the crowd and pass between two market stalls that are selling fake press passes and hookie G-Shock watches, and enter the Covered Walkway, a narrow alley that runs parallel to the main drag. It’s much quieter here, most tourists stay on Khao San.

I walk down the alley towards a little reggae bar. The air is thick and humid, and the cement floor feels slimy underfoot. I get to the bar – five stools arranged outside a rectangular hole cut in a corrugated metal sheet – and sit down. It’s muggy as hell and the mosquitoes are out, but the bottle of Singha I am served is absolutely ice cold. I sip the beer for a while, and Three Little Birds starts playing on the stereo. A hand comes to rest on my shoulder, it feels very warm. I turn round and see a face that I would come to love very much, smiling back at me.

I find it bizarre that the memory of this poignant and important moment in my life sometimes comes rushing back when I smell a very particular sort of drain stink. There were lots of smells in the alley that night: clove cigarettes, frying rice, sweat, incense sticks. But for some unfathomable reason my brain says ‘Nope. None of that. Drains are the key to this memory’. Occasionally I catch a whiff of the same smell on a London street, and everything I’ve just described is happening again in my head, for a fraction of a second, and it feels more like going back in time than recalling a memory.

Why are memories evoked by smell so powerful?

Aroma’s seeming ability to conjure up powerful memories is sometimes called the ‘Proust Phenomenon’, in reference to a passage in the author’s novel, Swann’s Way (1919) which describes an unexpected memory called up by accidentally dropping a piece of cake in a cup of tea:

“The memory suddenly appears before my mind. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before church-time) my aunt Leonie used to give to me, dipping it first in her own cup of real or lime-flower tea’, leading him to the conclusion that ’When from a long-distant past nothing subsists … the smell and taste of things remain poised for a long time … and bear unfaltering, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.”

Most people would recognise this phenomenon, and yet there is no definitive explanation for it (that I could find). However studies have been carried out, and their results point to a likely explanation related to our brain anatomy.

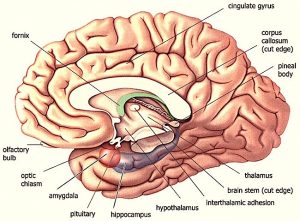

Smells are processed by the olfactory bulb, which is a neural structure that begins inside the top of the nose and runs along the bottom of the brain. The olfactory bulb has direct connections to two parts of the brain – the amygdala and hippocampus – which are strongly associated with memory and emotion. Our visual, tactile, and auditory sensory inputs do not pass directly through the amygdala and hippocampus, which points to our sense of smell having a ‘special relationship’ with emotion and memory.

A 1995 study (Herz and Cupchik) tested this theory by placing volunteers in an fMRI machine and imaging the amygdala while the subjects were shown pictures of familiar perfume bottles, and then exposed to the actual scents. The results showed the greatest activation in the amygdala and parahippocampal gyrus (a region surrounding the hippocampus) when exposed to the perfume, and suggest that odours which trigger strong, emotional memories also trigger elevated activity in the brain areas strongly linked to emotion and memory.

Other studies (Chu and Downes 2000; Willander and Larsson 2006) found that odour-cued memories tend to be older than verbal and visual-cued memories, with the most powerful being formed during the first decade of life – likely because we are born with powerful senses of smell and taste, while sight and hearing develop fully during the first year of life. Verbal and visual memories were found to peak in the second decade, from 11 – 20 years old, which might explain why the music we listen to during our teenage years tends to stay with us for the rest of our lives.

The same studies also found that this type of smell-evoked memory is much more vivid and intense than those triggered by words or images, with the effect of experiencing them frequently described as ‘going back in time’. It would seem that aroma is capable of evoking a stronger and more profound memory response because our nose is plugged directly into the memory centre of our brain in a way that our eyes, ears, and skin are not.

That’s all very interesting, but what am I supposed to do with it?

When I started researching this article, I wanted to find out why, from all of the aromas in the air during the episode I describe in the opening paragraphs, my brain picked the smell of drains as the one it would attach to that memory. I thought that perhaps certain types of smell are likely to trigger specific kinds of memory, and armed with such knowledge, I could present a method of selecting garnishes that would allow bartenders to pluck memories from their customers’ heads as they sip a cocktail. Unfortunately, it would appear that our brains are too messy and random for ‘surgical strike’ aroma garnishes, as none of the papers I read even mention this aspect of the smell-memory phenomenon. It could simply be a case of the ‘strongest smell wins’ as a memory is being formed and attached to an aroma.

However, I noticed that the science refers to this type of memory as ‘autobiographical memory’. It seems that our sense of smell being so closely associated with the centres of memory and emotion means the kind of memory that aroma evokes generally concern significant and formative things that happen to us. Smell-memories seem to be more powerful because they are attached to impactful past events that made us become who we are now.

However, I noticed that the science refers to this type of memory as ‘autobiographical memory’. It seems that our sense of smell being so closely associated with the centres of memory and emotion means the kind of memory that aroma evokes generally concern significant and formative things that happen to us. Smell-memories seem to be more powerful because they are attached to impactful past events that made us become who we are now.

This is a wonderful place to start when setting out to create a recipe, be it for a cocktail competition or a new menu. Competitions often ask bartenders to express themselves somehow, and a drink that has its roots in one of your most powerful and significant memories, served along with a presentation that describes the formation of that memory, can’t fail to do well.

It also struck me as useful to know that the most powerful smell-memories are formed when we are very young. Lucky as we are to live in a stable and safe part of the world, early life for most of us was probably quite similar in some respects. A smell from your childhood that conjures a powerful memory, perhaps cut grass during Summer holidays, or for city kids, the smell of rain on concrete during Summer holidays, might trigger a different but equally powerful memory in someone else. If you are at all interested in playing with aroma, this could be an interesting and slightly different place to start.

And if you find nothing else practicable in this article, at least you now know what ‘Proust Phenomenon’ is, should it come up in a pub quiz. Actually, ‘Proust Phenomenon’ is quite a good name for a cocktail…

Further Reading

Memory and Plasticity in the Olfactory System: From Infancy to Adulthood

Proust nose best: Odors are better cues of autobiographical memory